Last weekend, I had the opportunity to visit the exhibition ‘Fallen Angels’ by Anselm Kiefer at the Palazzo Strozzi in Florence. As I’m always drawn to art and architecture that resonate with me, this visit was no exception. The show combines both old and new works, featuring vast mixed media pieces that showcase Kiefer’s unique style. The Palazzo Strozzi itself has a timeless elegance, with its minimalist design and symmetrical architecture.

However, Kiefer’s works are anything but understated. The exhibition is incredibly tactile, with shiny gold leaf and textured materials like lead and sunflower seeds.

The canvases, layered with thick paint and featuring intricate details, slowly undergo a transformation as they interact with the environment, as the gold leaf and tactile surfaces gradually change over the course of the exhibition.

Typically for Kiefer, who embodies metamorphosis in his paintings, the work is left exposed to the elements, allowing for a natural decay that embodies the paradoxical relationship between destruction and creation.

It’s a thought-provoking exhibit that challenges the viewer to consider the beauty in chaos and the power of transformation.

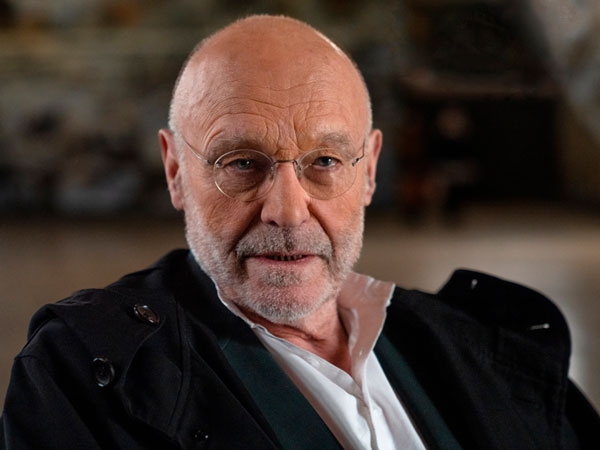

About Anselm Kiefer

Born in 1945 in Donaueschingen, Germany, Anselm Kiefer is one of the most important and versatile artists working today. His artistic practice incorporates diverse media, including painting, sculpture, photography, woodcut, artist’s books, installations and architecture.

Kiefer studied law and romance languages before pursuing studies in fine art at academies in Freiburg and Karlsruhe. As a young artist, he entered into contact with Joseph Beuys and participated in his action Save the Woods (1971).

Early works confronted the history of the Third Reich and engaged with Germany’s post-war identity as a means of breaking the silence over the recent past. Through parodying the Nazi salute or visually citing and deconstructing National Socialist architecture and Germanic heroic legends, Kiefer explored his identity and culture.

From 1971 until his move to France in 1992, Kiefer worked in the Odenwald, Germany. Throughout this time, he started incorporating into his work materials and techniques which are now emblematic–lead, straw, plants, textiles and woodcuts–along with themes such as Wagner’s Ring Cycle, the poetry of Paul Celan and Ingeborg Bachmann, as well as Biblical connotations and Jewish mysticism.

The artist first received major international attention for his work when he represented West Germany alongside Georg Baselitz at the 39th Venice Biennial in 1980.

The mid-1990s marks a shift in his work; extensive travels throughout India, Asia, America and Northern Africa inspired interest in the exchange of thought between the Eastern and Western worlds. Structures resembling ancient Mesopotamian architecture enter the work. Glimmers of Southern France’s landscapes appear, evidenced by depictions of constellations or the inclusion of plants and sunflower seeds.

An avid reader, Kiefer’s works are layered with literary and poetic references. These associations are not necessarily fixed nor literal, but rather overlap into an interwoven fabric of signification. The interest in books being both text and object is evident in his work. Since the beginning of his practice, artist’s books have constituted a significant part of his oeuvre.

Beyond making paintings, sculptures, books and photographs, Anselm Kiefer has intervened in various sites. After converting a former brick factory in Höpfingen, Germany, into a studio, he created installations and sculptures that became part of the site itself. A few years after his move to Barjac, France, Kiefer again transformed the property around his studio by excavating the earth to create a network of underground tunnels and crypts that connect to numerous art installations.

This studio-site is now a part of the Eschaton-Anselm Kiefer Foundation, which is open to the public. The opening of the foundation in 2022 coincided with Kiefer’s return to Venice, where a cycle of paintings inspired by the writings of Italian philosopher Andrea Emo was installed at Doge’s Palace, shown in parallel to the biennial.